Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon won the Golden Lion Venice Film Festival in 1951. Although it is a monochrome film, its visual beauty has never gone out of fashion. And, the film’s unique narrative structure is well worth to watch again.

One Crime, Four Truth

In one wood during the Heian period, a samurai couple pass by while the bandit Tajomaru is taking a nap. Tajomaru spots the wife and tricks the husband into tying her up and raping her in front of him. A short time later, the husband’s corpse was left at the scene and the wife and bandit were nowhere to be found.

The story revolves around the murder and is based on the testimony of witnesses, a woodcutter and a traveling priest, a captured bandit and the wife of a samurai, and the spirit of the dead samurai, summoned by a priestess. However, the witnesses differ in their accounts of the case, so it is not clear which is the truth.

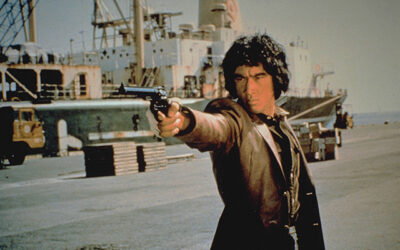

The Bandit’s Story

Tajomaru, the bandit and a notorious outlaw, claims that he tricked the samurai to step off the mountain trail with him and look at a cache of ancient swords he discovered. In the grove, he tied the samurai to a tree, then brought his wife there with the intention of raping her. She initially tried to defend herself with a dagger but was eventually overpowered by the bandit, and eventually seduced by him. The wife, ashamed, begged the bandit to duel to the death with her husband, to save her from the guilt and shame of having two men know her dishonor. Tajomaru honorably set the samurai free and dueled with him. In Tajomaru’s recollection, they fought skillfully and fiercely, with Tajomaru praising the samurai’s swordsmanship. In the end, Tajomaru killed the samurai and the wife ran away after the fight. At the end of his testimony, he is asked about the expensive dagger used by the samurai’s wife. He says that, in the confusion, he forgot all about it, and that the dagger’s pearl inlay would have made it very valuable. He laments leaving it behind.

The Wife’s Story

The wife tells a different story to the court. She claims that Tajomaru left after raping her, she begged her husband to forgive her, but he simply looked at her coldly. She then freed him and begged him to kill her so that she would be at peace but he continued to stare at her with loathing. His expression disturbed her so much that she fainted with the dagger in her hand. She awoke to find her husband dead with the dagger in his chest. She attempted to kill herself but failed.

The Samurai’s Story

The court then hears the story of the samurai told through a medium. The samurai claims that, after raping his wife, Tajomaru asked her to travel with him. She accepted and asked Tajomaru to kill her husband so that she would not feel the guilt of belonging to two men. Shocked, Tajomaru grabbed her and gave the samurai a choice of letting the woman go or killing her. “For these words alone,” the dead samurai recounted, “I was ready to pardon his crime.” The woman fled, and Tajomaru, after attempting to recapture her, gave up and set the samurai free. The samurai then killed himself with his wife’s dagger. Later, someone removed the dagger from his chest, but it is not yet revealed who it was.

The Woodcutter’s Story

Back at Rashomon (after the trial), the woodcutter states to a commoner that all three stories were falsehoods. The woodcutter says he witnessed the rape and murder but he declined the opportunity to testify because he did not want to get involved. According to the woodcutter’s story, Tajomaru begged the samurai’s wife to marry him but the woman instead freed her husband. The husband was initially unwilling to fight Tajomaru, saying he would not risk his life for a spoiled woman, but the woman then criticized both him and Tajomaru, saying they were not real men and that a real man would fight for a woman’s love. She urged them to fight one another but then hid her face in fear once they raised swords; the men, too, were visibly afraid as they began fighting. In the woodcutter’s recollection, the resulting duel was far more pitiful and clumsy than Tajomaru had recounted previously; Tajomaru ultimately won through a stroke of luck and the woman fled. Tajomaru could not catch her but took the samurai’s sword and left the scene limping.

The Rashomon Effect

The investigation into the case comes to a standstill when a victim, the victim’s wife and a perpetrator, the bandit, give three different accounts of the murder. It is that the woodcutter knows the truth and all three were lying. The film’s narrative structure has come to be known in psychology and legal circles as the Rashomon effect.

Originally, this structure is derived from Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s “Yabu-no-Naka” (In the Woods).

Yabu-no-Naka

Media Type: Comic

Author: Ryunosuke Akutagawa

Availability: CDJapan

Monochrome Beauty

Kazuo Miyagawa’s “Gray Color”

Rashomon is arguably one of the world’s best monochrome films. This would not have been possible without photographer Kazuo Miyagawa. He was particularly concerned with grey color. His theory was that monochrome films are simply two shades of black and white, but in the grey between them there are infinite colors.

He was instrumental in changing the atmosphere of his work through his use of grey. In particular, his use of natural light, capturing winds, rains and heat of the sun in black and white, was so brilliant.

SUNTORY corporate commercial filmed by Kazuo Miyagawa

Innovative Camera Works

Rashomon was a turning point in their film careers, both for Kurosawa and Miyagawa.” Described as “a camera went into the forest at the first time”, there were many innovative experiments in the film.

The first difficult request from Kurosawa was to shoot the film with the sun in the frame. At the time, it was taboo to point the camera at the sun, but to meet this request, he came up with the idea of filming the sun shining brightly through the trees, which produced a vivid, dramatic image.

Miyagawa also suggested to Kurosawa that he wanted to create a film with “a strong contrast between black and white”, which was adopted. To achieve this, Miyagawa came up with the idea of using mirror lighting instead of the conventional reflector,

which resulted in an image full of energy that astonished the world.

We are Humans, After All?

Human Stupidity

Rashomon also gives great significance to its final scene, particularly with regard to human nature.

Under the Rashomon, the woodcutter tells the court that the testimonies of the bandit, the samurai and the samurai’s wife are all wrong and that what he has seen is the truth, but in fact even he is also lying, as the commoner points out.

All four witnesses thus distort the story to suit their own convenience. Rashomon sets its scene in the turbulent Heian period, effectively depicting the human psyche and the inability of people to trust each other.

Akira Kurosawa and Ryunosuke Akutagawa, the author of the film, borrowed from the turbulent Heian period to express the ambiguity and emptiness of what human beings can do.

Human Tolerance

There is a scene at the end of the film where the woodcutter tries to bring home a baby left at Rashomon. He says that he has six children, and whether he raises six or seven, the hardship is the same. But the travelling priest does not trust him, who has given false testimony, and blames the woodcutter for this.

In the end, however, the travelling priest is defeated by the woodcutter’s persuasion and is ashamed of his own self-belief that he can no longer trust people. Then the rain stops and the film reaches its finale.

Negative opinions were raised about the baby episode inserted at the end of the film. However, Kurosawa clearly denied this opinion, saying as follows:

“Humans have to believe in Humans to live.”

Rashomon Digital Full Version

Media Type: DVD

Producer: Akira Kurosawa

Language: JP

Availability: CDJapan